- Home

- Sarah M. Broom

The Yellow House Page 2

The Yellow House Read online

Page 2

Before it was the Yellow House, the only house I knew, it was a green house, the house my eleven siblings knew. The facts of the world before me inform, give shape and context to my own life. The Yellow House was witness to our lives. When it fell down, something in me burst. My mother is always saying, Begin as you want to end. But my beginning precedes me. Absences allow us one power over them: They do not speak a word. We say of them what we want. Still, they hover, pointing fingers at our backs. No place to go now but into deep ground.

MOVEMENT I

The World Before Me

The things we have forgotten are housed.

Our soul is an abode and by remembering houses and rooms, we learn to abide within ourselves.

Gaston Bachelard

I

Amelia “Lolo”

In the world before me, the world into which I was born and the world to which I belong, my grandmother, my mother’s mother, Amelia, was born in 1915 or 1916 to John Gant and Rosanna Perry, a shadow of a woman about whom only scratchings are known. Even the spelling of Rosanna’s name is uncertain. She appears briefly in Lafourche Parish census records for 1910 and 1920. These papers tell us that my great-grandmother lived in Raceland, Louisiana, could not read or write, and that she had been widowed. Next to my great-grandmother Rosanna’s name, no form of work was ever indicated. Those are the facts as they were recorded, but this is the story as the generations tell it.

Rosanna Perry had these five children: Edna, Joseph, Freddie, my grandmother Amelia, and Lillie Mae. Doctors had warned Rosanna that another child would kill her; still, Lillie Mae was born in August 1921 when Amelia was five or six years old. It has always been said that my great-grandmother Rosanna Perry died in childbirth when she was thirty-four, but those who might know are not alive to confirm, deny, or offer alternative theories, and burial records cannot be found. Whatever the facts, Rosanna disappeared.

Of Rosanna’s children, the only one ever to reside under the same roof with her was the son Joseph. Where her other four children went after being born, why they went, and with whom they lived is uncertain. And so even if Rosanna did not die giving birth to Lillie Mae, my grandmother Amelia still would not have had a mother.

Grandmother was born on Ormond Plantation, named after an Irish castle, next to which the West Indies colonial–style Louisiana replication would appear bedraggled and dim. Ormond sits haughtily still, it doesn’t care, along Louisiana’s River Road, seventy miles of two lanes hugging tight to the curves of the Mississippi River, its waters hidden behind levees that look like molehills. The “fabled Great Mississippi River Road,” present-day brochures call it. Its “showy houses, gay piazzas, trim gardens, and numerous slave-villages, all clean and neat,” read the description during its pre–Civil War heyday when tons of “white gold” sugarcane were grown and processed in Louisiana, building generational wealth and power for white plantation owners.

What modern marketers never tout is how in 1811 the largest slave revolt in American history, an army of five hundred or so, wound its way along the River Road for two days, strategically headed toward New Orleans to take over the city, stopping only to light plantations afire after loading up on weaponry. They made it far, considering—twenty of forty-one miles—before a local white militia halted them. Some slaves escaped; others were shot on the spot. Of the unlucky ones put on trial, most had their heads severed and placed on poles atop the River Road’s levees—forty miles of heads, the grisly trophies of petrified whites.

Today, the “pillared splendor” (as a recent brochure describes) of the River Road’s plantations is flanked and outmatched by petrochemical refineries, their silver nostrils blowing toxic smoke.

Long before the near-to-end when my grandmother would forget her life’s story, she claimed July 1916 as her birth date even though it was officially recorded a year or two after the fact. Fixed details were important to stories, Amelia knew, even if you couldn’t prove them.

She was named after her father, John Gant’s, mother, Emelia, whom she would never meet. Grandmother’s namesake presided over a large family who had spent all of their lives in St. Charles Parish, where Ormond Plantation is, in a town now called St. Rose but was then called Elkinsville after freed slave Palmer Elkins, who in the 1880s made for himself and his family a self-sufficient community composed of four dirt streets, named in the order in which they appeared: First, Second, Third, and Fourth. The Gants were tall, brooding men well known in the community. Samuel Gant, brother to Amelia’s father, was pastor of Mount Zion Baptist, Grandmother’s church in her later years, where her funeral service would be held and where her son Joseph still serves as deacon.

Sometime in Amelia’s childhood, no one is sure exactly when, she left St. Rose where she was born for New Orleans, a thirty-minute drive away, to live with her eldest sister. Edna had married Henry Carter, whom everyone called Uncle Goody. Edna was a Jehovah’s Witness, the young Amelia her right hand, toting Watchtower bulletins around city streets on long soul-saving sprees that netted few returns. Amelia never converted; she had the kind of mind to resist.

Edna and Uncle Goody lived uptown on Philip Street in a community of women where everyone called themselves something other than their given name, it seemed, where familial relationships were often based on need rather than blood. What you decided to call yourself, these women seemed to say, was genealogy too.

The disappeared Rosanna Perry had two sisters who were part of this community. People called her eldest sister Mama. Mama also answered to Aunt Shugah (Shew-gah), a supposedly Creolized version of Sugar except it is actually only a restating of the English word, the stress moved elsewhere. Aunt Shugah’s actual name was Bertha Riens. She was also sister to Tontie Swede, short for Sweetie. Aunt Shugah was the biological mother of a woman who only ever called herself TeTe, with whom Amelia shared a sisterhood even though they were cousins.

These women, who lived in close proximity, composed a home. They were the real place—more real than the City of New Orleans—where Amelia resided. In this world, Amelia became Lolo, another version of her name entirely, the origins of which no one can pinpoint. Everyone called her Lolo, no one uttered her given name again, not even her eventual children, which exacted on the one hand a distance between child and parent and on the other an unnatural closeness and knowing.

Lolo’s life contains silent leaps with little tangible evidence to consult. But then flecks of story appear: Grandmother was a young girl living with her sister Edna, then suddenly she was fourteen years old and living in a boardinghouse on Tchoupitoulas Street in the Irish Channel neighborhood of New Orleans.

Along with a teenage Lolo in the boardinghouse lived John Vaughan and his wife, Sarah McCutcheon, the woman Lolo would come to call Nanan and regard as her mother and whom Lolo’s children—Joseph, Elaine, and Ivory—would call Grandmother. She was Sarah Randolph by birth and Sarah McCutcheon by marriage; she was not a blood mother to Lolo, but she acted with the rights and liberties of one. Sometimes, when Sarah McCutcheon was upset she’d say, “I’m Aunt Carolina’s daughter,” but no one had any idea who Aunt Carolina was. And no one dared ask. It seemed an astounding riddle.

Two stories get told about Sarah McCutcheon: that she raised Lolo and that she once owned a restaurant that closed after a man she loved ran off with all her money. But before that, Sarah Randolph married Emile McCutcheon and they lived briefly together in St. Charles Parish. This must be how Sarah McCutcheon came to know Lolo’s father, John Gant; or how she came to know Lolo’s mother, Rosanna Perry.

Lolo learned from Sarah McCutcheon how to find the numinous in the everyday. It was from her that Grandmother learned to dress the body and dress a house like you would the body. How she saw firsthand that cooking was a protected ritual, a séance really. Grandma McCutcheon had this big potbelly stove, black cast iron. It was the best food I’ve ever eaten, period. Meatballs with tomato gravy, stewed chicken, stew meat with potatoes. She’d make her own biscuits

from scratch. She’d make root beer and put it in the bottles. She’d get these tomatoes, you didn’t even know about no lettuce. She sliced these tomatoes so thin, put them in a bowl with vinegar and sugar. You’d be drinking the juice. That’s my mother, Ivory Mae, speaking for herself.

Cooking had to be done right because food carried around in it all kinds of evil and all kinds of good just waiting to be wrought. This was why, for instance, before you ate a cucumber you rubbed the two ends of it together to get the fever out. And why you always cooked the slime all the way out of the okra before you served it. Why? You didn’t ask, because inquiry from children or young people toward an elder was not allowed. You didn’t make eye contact with adults either. You spoke to other children if you were a child. These were protections.

But even if you could ask why, Sarah McCutcheon would likely say, “Because they said.” “They” were omniscient and omnipresent, requiring no explanation.

Each meal was a creation, derived from scratch, the smell and taste unified. Sarah McCutcheon painstakingly taught Lolo this. Lolo would teach her three children, too. Whatever seasoning my mother and her brother and sister chopped for food had to be so fine it would not be visible in the finished dish. Chunky meant unrefined, that care had not been taken, that the thing was done in haste. If it did not look appetizing, Sarah McCutcheon taught Lolo—and Lolo taught her own children—it could not be good to eat, and this small germ of an idea that appearance determines taste settled deep, especially in my mother, Ivory Mae, who to this day does not eat what does not appear right.

At fourteen, Grandmother had not been to school within the past year, according to 1930’s census documents. She had dropped out after fifth grade but could read and write. And she knew, above all, how to work, which is always the beginning of fashioning a self.

Lolo worked for what she wanted, but what she set her sights on was always changing. She was practical, known to tell an aspiring but not-quite-there person, “You got champagne taste with beer money.” The matriarch of one family she cleaned for was always giving Lolo her old china, her elaborate heavy curtains. These beautiful, sometimes fragile things had to be handled a certain way. They were the kinds of objects that slowed you down, could take some of the crass out of you. This family nurtured but did not ignite Lolo’s love for beautiful things. That had come from Sarah McCutcheon, long before.

Lolo placed men in the category of beautiful things. Lionel Soule was one. A married man, a devout Catholic whose wife was unable to have children, he fathered Lolo’s three—Joseph, Elaine, and Ivory—but was present in name alone, bestowing upon Elaine and Ivory a last name, Soule, which in the right company spoke something about them. Lionel Soule was descended from free people of color; his antecedents included a French slaveowner, Valentin Saulet, who served as a lieutenant in the colonial French administration during the city’s founding days. Having a French or Spanish ancestor confirmed your nativeness in a city colonized by the French for forty-five years, ruled by the Spanish for another forty, then owned again by the French for twenty days before they sold it to America in 1803, a city where existed as early as 1722 a buffer class, neither African and slave nor white and free, but people of color who often owned property—houses, yes, but sometimes also slaves, at a time in America when the combination of “free” and “person of color” was a less-than-rare concept. This group—often self-identified as Creole; claiming a mixture of French, Spanish, and Native American ancestry; passing for white if they could and if they chose—had been granted access to the kinds of work held only by white people: in the arts (painting, opera, sculpture), or as metalworkers, carpenters, doctors, and lawyers.

This was partly why my Uncle Joe, though Lionel’s son, was confused and disappointed about having been given his mother’s maiden name, Gant. He claims he thought he was Joseph Soule up until he was a grown man in the navy, when the sergeant called out Joseph Gant, the name on his birth certificate, causing him to look around “like a stone-cold fool,” he says now. When he asked his mother why he carried his grandfather’s last name she said, “You lucky you had a name.”

Lolo was dark skinned and fine with big thick legs that men loved to grab hold of. There is a single image of a young Lolo—her hair slicked back with curled-under bangs running the width of her forehead—taken at Magnolia Studio, the only black-owned photo studio in the city. It had the best-dressed waiting room. To advertise, they hung along the outside and inside walls images of “folks small and great.” If you wanted to know whether a person you’d met on the street was somebody, you checked for their image on the walls of Magnolia Studio.

In her photo, Lolo wears horn-rimmed cat-eye glasses and a pastel-blue dress with white accents on the collar and on the pockets. Her shoes are dazzling red—the photographer painted them so—her ankles thick in the pumps. She stands tall, one arm on top of a pillar serving as prop, her hand partly open, the other on her right hip. She has what my mother calls dancing eyes, what I call laughing eyes. Instead of smiling, she just knows.

Lionel Soule glimpsed his two eldest, Joseph and Elaine, only a few times in rushed transactions when my grandmother appeared at his dock job to collect folded-up money from his palm. Auntie Elaine remembers this one detail: “With every word you could hear his fake teeth going click, click, click.” In her earliest years, my mother thought the following about her father: I didn’t know I had no daddy. I thought I just came here. I swear. I thought he was dead. I assume if he ain’t around, he must be dead. Which explains why when the one time her father, Lionel, came to visit, my mother ran and hid herself behind a door. Rather than wait for her or persuade her to come out, Lionel Soule left and never came back. Ain’t that the pitifullest thing you ever heard?

II

Joseph, Elaine, and Ivory

Grandmother named my mother Ivory after the color of elephant tusk. Those who are still alive to tell stories say Grandmother, who was twenty-five when Ivory Mae was born, became infatuated with elephants during frequent lunch breaks at the Audubon Zoo, which was within walking distance of a mansion on St. Charles Avenue where she once worked.

Uncle Goody called the child not by her coloration, Ivory, but by her birth year: ’41, the end of the Great Depression—the residue of which still mucked Uncle Goody’s life. Ivory’s nickname had the weight of a history Uncle Goody could not shake, which Ivory Mae understood made her highly significant, to Uncle Goody at least. “Where Old Forty-One?” he would always say.

Forty-One! The year of my birthday was what he called me. Here come Old Forty-One. I used to like it. I used to get so happy.

It paid to be his chosen. Uncle Goody worked on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad cleaning boxcars and lining them with wood. Sometimes he oiled the railcar brakes. At home, he presented another self, making molasses candy that stretched long like taffy. When Ivory Mae was around, she was always the first to taste. That was the first time I knew that men knew how to make candy.

Joseph, Elaine, and Ivory: When people said one name, they almost always said the other two. Joseph was three years older than Elaine, and Elaine was two years older than Ivory. The trio formed a small intimate band closed for membership.

Everyone knew that Joseph, Elaine, and Ivory belonged to Lolo, not by coloration, which could throw off the undiscerning (they bore their father’s color), but by their manner and how they dressed. Of the three children, Elaine was darkest, and she was the color of pecan candy—a milky tan. They were starched children, their lives regimented, Lolo’s attempt to create for them a childhood she had not had. This was why in every place she rented, she painted the walls first, as if doing so granted them permanence, which was the thing she craved. She bought brand-new wood furniture that looked to have been passed down through generations—Joseph, Elaine, and Ivory sustaining the aura of antiquity with their daily polishings. She shopped in the best stores, always collecting beautiful things and storing them away to be used later. But these untouched passio

ns, boxes upon stacked boxes, succumbed to fire one night while the family stood on the sidewalk watching one of Lolo’s remade houses on Philip Street in the Irish Channel burn to the ground.

Of her history, Lolo seemed to know only her mother’s and father’s names and the names of those who raised her. She favored the moment, knew how remembering the past could elicit despair. For a long time, my mother says, Grandmother kept retelling the story of how she prayed unceasingly to see her mother, Rosanna Perry, in dreams. The vision took forever to manifest and when it did during sleep one night, the woman who appeared was a dead mother surrounded by a brood of zombified cousins. Grandmother, frightened by these corpses, was forced to rebuke the evil dead spirit, telling it to go away from her and never to return. All of this heightened because she could not rightfully identify the spirit in her dream, having never glimpsed her mother in life or in photograph.

The past played tricks, Lolo knew. The present was a created thing.

Maybe this was what led her to try her fate in Chicago around 1942, leaving six-year-old Joseph, three-year-old Elaine, and two-year-old Ivory behind with Aunt Shugah and her daughter, TeTe.

After Lionel Soule came a man called Son who drove cabs for the V-8 company, the only car service black people in New Orleans could call. Son left for Chicago in a rush. It is said that Grandmother flew to him there for a weeklong visit that became a yearlong stay. Lolo took a job in the bakery where Son worked. She planned to save, set up a decent life in a remade Chicago apartment, and send for her kids; but her leave-taking must have revived feelings of her own mother’s abandonment, her children now in the hands of the same group of women who raised her.

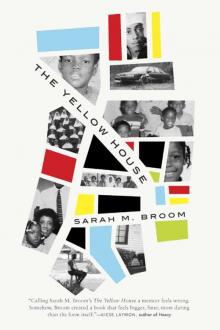

The Yellow House

The Yellow House