- Home

- Sarah M. Broom

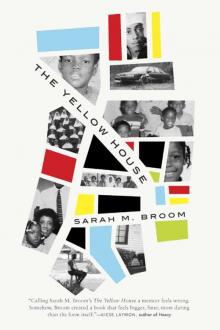

The Yellow House Page 4

The Yellow House Read online

Page 4

Every April twelfth on the Mission’s anniversary, each member spoke their “determinations,” what they intended to do for God and who they intended to be in the coming year. These speeches ran three or four pages, which led dedication services to extend far past midnight. I used to always sing this lil light of mine, I’m gonna let it shine. I used to say my desire is to be a nurse. I used to say that because Lolo was a nurse and I wanted to be like her.

Joseph wanted to be like his mother, too, but mostly in presentation, which he sometimes affected to the detriment and exclusion of other useful qualities. He was the only boy at Hoffman’s eighth-grade graduation who wore a tailor-made suit. It was gray with a collar and lapels hand stitched in a darker gray thread that made “a beautiful show,” Uncle Joe says. Everyone had to wear a suit, but most were store-bought. Those who couldn’t afford one still graduated, but they didn’t march with the class. Joseph’s suit from Harry Hyman’s shop on Rampart Street looked so rare that even teachers were complimenting him. “That was one of the high points of my life,” he says now, at seventy-six years old. He was six feet, four inches and narrow (and still is, wearing the same size clothes now that he did then). His hair waved up with water, which the girls liked.

That eighth-grade graduation suit and the attention it drew marked the start of Joe Gant’s lifelong love of clothes. He could dress better than the girls. Joseph’s obsession with preserving the creases in the pants he spent hours ironing, made him act strange sometimes. “I used to get dressed to go out and I wouldn’t ever sit down.” When he grew to driving age, he eased into his car reluctantly, the underside of his long legs barely grazing the seat, which forced him to drive through town straight backed, like a man in a perpetual state of alarm. “Some people think clothes do something for them, I thought I did something for clothes,” he told me. “I was cocky, in other words.”

Joseph spent his earnings from summer jobs on a wardrobe for high school that included tailor-made slacks and nylon underwear from Paris, which he bought from Rubenstein Brothers on Canal Street. Blacks couldn’t try clothes on then. Joseph went in knowing his size: 42 long or extra long, depending on the style; 36 sleeve; 16-and-a-half-inch neck. He also bought the ties all boys were required to wear at Booker T. Washington High School. If you forgot the tie, you wore one of the old ones collected in every classroom for those who couldn’t afford it. “I didn’t wear any of that shit. I had my own tie. It did a lot for your manlihood and thing,” he said. “Something about the tie gave me a sense of importance, a sense of being extra-special like.”

Joseph wore tailored suits, but Elaine and Ivory made their outfits. Sewing was making a self, and this Ivory Mae especially loved. Even in middle school sewing classes, she had an eye for the movement of clothes on a body and could decide the right special touch, always improvising patterns with a surprising detail that set her apart.

Young women learned fashion from each other, mostly on the streets, but also at Ebony Fashion Fairs held yearly at the Municipal Auditorium where the women attendees dressed so hard that they outshone and lost regard for the models parading onstage, who wore unattainable things. Ivory Mae was never much for the outlandish, anyway. Her style was deceptively simple, her clothes flattering the right curves. Dresses you might wear for special occasions she wore every day. In this way she and Joseph were alike. They dressed to be seen, which is how it came to be that they built up a reputation for floor showing, as Uncle Joe calls it. “Yeah, we knew we looked good.” They danced wherever there was a floor—a bar or a ball. The sidewalk, sometimes. “We used to go in clubs and start dancing from the door. For a poor man I used to dress my can off,” he says. “That’s what used to get me in so much trouble and thing with the ladies.”

He and his baby sister, Ivory, would swing it out, jitterbugging and carrying on. Ivory was always fun and always light on her feet. She was especially gifted at being led and men generally loved this quality in her. Sometimes Ivory would enter a club where she was to meet Joseph already dancing a number, the two of them working up to each other, the drama of which could cause a commotion. “Once we touched each other,” Uncle Joe says, “it was on. People be dancing, they get off the floor and let us dance, knowing we gone clown. People who didn’t know us thought we were some kind of celebrity, making all them different turns and thing. I’d turn her with my hand. Sometime I’d have my back to her and catch her hand and spin her round two, three times, maybe do a lil split or something like that, you know, common stuff.”

They were wild about improvisation, enacting their ideal freedom, which was precisely why Grandmother never wanted to dance with her son Joseph. “Boy, dance straight,” she would always say. “You clown too much.”

No one clowned more than another boy in the neighborhood who always stole the show. His name was Edward, but those who knew him only ever called him by his last name: Webb.

III

Webb

Most people just couldn’t see no matter how hard they turned it how Webb and Ivory Mae got tied together. They were not even boyfriend and girlfriend, but back in those days no one ever seemed it anyway. Quiet often meant sneaky, but as far as people knew Ivory Mae was a faithful student at Booker T. Washington High, the kind teachers always cast their vision upon; she was going to be somebody.

About Webb, little of an academic nature could be said. “If he had a following he could have been a comedian,” Uncle Joe, who was several grades ahead of him, says now. Webb sometimes stammered when he spoke, but this only encouraged his style, made him the type of person everyone knew if not liked. Webb had the build of a quarterback, which he was. He wasn’t no main player, but he was there, he had on a uniform.

Webb and Ivory Mae grew up together, barely a street apart. Webb was the third of Mildred Ray Hobley’s children, the only boy, brother to Minnie, Dawnie, and Marie. His sisters called him Lil Brother. He was one year older than Ivory Mae and knew her from the time she wore white ruffle socks in hard-soled training shoes. They could have passed for brother and sister in terms of complexion and high-flying personality, but look: Mildred had dreams for all of her four children. Webb marrying Ivory Mae was not one of them.

He was crazy about her though. Could not get enough of just looking in her face. And his cousin Roosevelt was sweet on Elaine, the tomboy. For the most part, Ivory Mae couldn’t stand Webb; he got on her nerves, bad. To her, he was a trying-to-be trickster, always thinking he was funnier than he was. There she would be on the porch, pretending aloofness when he would come loping over, pigeon-toed-like, he’d do all kind of dances on the sidewalk. He had a small dog that he knew Ivory Mae despised. His idea of being playful was to throw the dog at her, tell the dog Get her, get her, get her, which would make Ivory mad at first but then happy, secretly, later. They had between them the kind of intimacy born of growing up near another person and thus taking them for granted. Later on, once they were boyfriend and girlfriend, they sat on the porch kissing in plain sight.

Tenth grade was over and it was summertime, which meant you hung out more, tried to figure out what else to do besides look. Now Ivory Mae wanted to know what came next, after the kissing. Webb and I were just fooling around, like friends, you know, teaching and learning. We were going to school and learning about the birds and the bees and then I was pregnant. It was really just one time that we were intimate. It wasn’t no big love affair.

In those days, children did not speak openly to their parents. “Get out from grown folks’ business,” you were told. Whatever we found out, we found out on our own. In hindsight, there were the platitudes, like keep your dress down and your legs closed, but it was not clear what this meant, whether this was about sitting on a bus while wearing a dress or sex. The latter would not have automatically crossed Ivory Mae’s mind, but she was impulsive when she wanted, drawn to instant gratification, the kind to listen later.

After Ms. Anna Mae, a family friend from the apartments back behind their house, took Ivory

Mae to Charity Hospital where the doctor confirmed her pregnancy, Grandmother marched over to Mildred’s house and worked out the details.

If Lolo was disappointed, she did not say.

In September 1958, when Ivory Mae would have begun eleventh grade and Webb his senior year, they were married instead, standing in the living room of TeTe’s house on Jackson Avenue, surrounded by Elaine and Roosevelt, Mildred and Lolo, and Webb’s sisters. Webb had traded in his football jersey for a groom’s dark suit and tie. He had his nice lil shoes on. I was decked out like a lil bride. We was doing it up. Ivory had borrowed a white wedding dress and veil from her brother Joseph’s married girlfriend, Doretha. She wore brand-new white shoes. Her attire was appropriate for the time, but when she looks back at it: I really didn’t need to have no wedding gown. I could have worn something I already had. No wonder Webb’s people ain’t like me.

But Mrs. Mildred was not the sort of woman to dash a young girl’s feelings. She meant to have a strong say in the marriages of her children, but this one time things had gone awry. She had already forbidden her three girls from even looking in the direction of Joe Gant. Even as a boy, he didn’t always own his actions. Instead of saying, for example, that he moved in with a woman, he would say the woman came to him and “got his clothes a piece at a time and brought it to they own house. Now that’s gospel.”

These were the no-good, have-nothing ways Mildred’s children were to avoid. “I didn’t have enough money for them,” Joe Gant says. “She didn’t want her daughters talking to nobody in the neighborhood who she thought wasn’t going nowhere. Your mama wasn’t in they class either.”

Her light skin and hair, things that Ivory Mae thought made her special, meant nothing to Mildred and her family who had the same features. Ivory wasn’t judged to be going anywhere from the looks of it, and now here was evidence. She had ruined things for Webb, and this notion, sprinkled especially by his sisters, settled in the family, corrupting even the sweetest impulses of the young couple who tried to play the part, now that the baby was coming.

The couple spoke their vows. Webb slipped onto Ivory Mae’s finger rings his mother had been given by her own mother. An engagement band and the wedding ring both went on at the same time.

It wasn’t no party after. Cake and ice cream and everybody went about they business. We went out somewhere to some lil club or some kind of craziness, our lil black clubs around Washington Avenue. There they might have seen Ernie K-Doe perform, long before he had a name, before he built the Mother-in-Law Lounge, his permed hair made mythic. No, this was back when he still performed in tennis shoes, which were considered improper for a singing man, before he could afford leather. When he finally got a record, people said he could buy him some shoes now.

They courted after the wedding. Movies and dancing at the Blue Door and Tony’s down on St. Peter, outside the French Quarter, across Rampart, where black people could go. The Pimlico Club where another high school dropout, a girl named Irma Thomas, sang. That was when music was normal and natural as Mom calls it, just coming from within you. Back in the clubs, Mom looking sharp with the other girls her age—she still wasn’t showing—they posed for photographs standing around a pinball machine. Of course we were silly, giggling.

Instead of school, Ivory Mae walked around the corner to her good friend Rosie Lee Jackson’s house. Rosie Lee was the one girl she knew who had already gotten pregnant, already gotten married, already had a baby.

I think that’s why I like cabbage so much now, cause she look like she was always cooking cabbage. I used to climb on her bed after I ate and sleep.

Ivory missed school. She was always running into former classmates. No one could believe it: Ivory Mae, of all people. Lying on Rosie Lee’s bed, Mom nursed small desires while her belly grew. She planned to return to Booker T. Washington after the baby arrived; she knew other girls who had done this.

Webb spent his days chasing work or working construction jobs with his stepfather, Nathan Hobley, a brick mason who laid French Quarter courtyards and with whom he barely got along. Webb had a hard time being serious. Nathan Hobley would hold mock job interviews at the kitchen table, Webb sitting across from him, failing.

As a married couple, Webb and Ivory Mae had a room in Nathan and Mildred’s house in New Orleans East, on Darby Street, an out-of-the way, semi-industrial section off Old Gentilly Road. Nathan was an astute businessman, pioneer minded, owning several houses in the East before it was common for black people to do so. But being in Mildred’s house made Ivory Mae feel hemmed in. It was a place I really didn’t have anywhere to go. The house was nice enough. It sat back off the street, but it was in the country as Ivory Mae saw it. None of her friends lived there. She was always calling somebody to bring her back to town, by which she meant the city, to Dryades Street in Central City, where Grandmother and Mr. Elvin had moved to another rented house. She was small with a tiny belly up until the last few months when she swelled suddenly with Eddie, who was a huge child, nearly nine pounds, with a square head shaped just like his father’s.

When I brought him home nobody thought he was a baby, looked like he could have been a month old. Eddie was a serious infant, inquisitive. He was a wide child and terribly hungry from his first day on earth. My mother attempted to breastfeed him but so ravenous was he that she gave up. He look like he never had enough. You could hear him sucking from a mile away. His insatiable thirst ruined it for all eight of the children who would come after. The memory of his sucking and gnawing created such torment that Ivory Mae could not bring herself to breastfeed again.

Just after Eddie was born, Booker T. Washington High School changed its policy. Mothers were no longer accepted. Ivory Mae could, the school suggested, finish at a special school for delinquents, for messed-up kids, but she couldn’t see being set apart in this, the wrong way. She pleaded with the principal to please make an exception and take her back, but she was a poor example for the other girls now. Nothing about her looks and charm could change that, he said. She had entered womanhood, her first dream of finishing high school and going to college dissolved.

In May, a few months after Eddie was born, Webb enlisted in the army. He was sent to South Carolina’s Fort Jackson for basic training and then to Fort Hood, Texas, where he was stationed. When he left New Orleans, Mom was pregnant again with a boy she would name Michael. She was pregnant when she and Webb married and pregnant when he died.

The circumstances of Webb’s death, a shortened version of which was reported to Ivory Mae the morning of November 1, 1960, were summarized this way in the investigator’s statement:

On 31 October 1960, approximately 2320 hours, Pfc Edward J. Webb … Company C, 6th Infantry, 1st Armored Division, Fort Hood, Texas, was walking west on the right side of highway 190, in the city limits of Killeen, Texas, with two other members of his unit. While walking in the right lane of a four-lane road, WEBB was struck, from the rear, by a vehicle driven by Sp4 Ervil J. HUGHES … who fled the scene without making his identity known. WEBB was pronounced Dead on Arrival at the US Army Hospital as a result of the injuries sustained in this accident.

Everyone knew that Webb could have a temper. Even in his hometown with people that he knew. His own stepfather hired and fired him from construction jobs repeatedly, because he couldn’t take directions. And he liked to drink. People could see him getting into a row at a bar in the back parts of Fort Hood because sometimes, in his fearlessness, he didn’t know when to stop. He might have pushed the wrong man too far. Back home, theories swirled about Webb’s death. The army provided almost no detail. Most of his family and friends insisted that it was racially motivated, had to be, I mean, just look at the bare facts: black man run over while walking home, no explanation whatsoever, no fuss, no arrests.

The epicrisis, a more narrative summation appended to Webb’s autopsy report, reveals slightly more detail:

It is understood by word of mouth that this young colored Enlisted Man was walking in t

he middle of the pavement on Route 190 in Killeen and was under the influence of alcohol. This behavior terminated in a car hitting and felling him to the ground. His colleagues at the side of the road were confused by the accident and did not seek either to remove him from the roadway and/or to stop traffic running over him. Instead, they tried to wave down cars to obtain assistance. Then, a car ran over the body of Webb as he lay in the road … Alcohol appears to have either released a suicidal trait in the deceased or to have made him unaware of the dangers of walking in the path of traffic.

A map drawn in a later court case that charged the hit-and-run driver with negligent homicide indicates that it was a dry, moonlit night with broken clouds. Webb’s left shoe was knocked off of him when he was catapulted many feet into the air before dropping down onto concrete pavement that was, according to this map, in “excellent condition.” The driver was never convicted.

His official cause of death is listed as “cerebral concussion and subarachnoid hemorrhage.” Webb was eighteen years, ten months, and seven days old, two months away from his birthday on Christmas Day.

On the death certificate, listed both as “next of kin or next friend” and “wife” is Ivory Soule Webb, address 4116 Darby Street, New Orleans.

Lying there in the casket, Webb looked three times his age. His skin was darker than Mom had remembered, his head swollen due to the circumstances of his dying. She stood there looking at her husband of two years, but really he was her childhood friend of forever. They had lived together as husband and wife in the same house for less than a year before his enlistment. What was there between them now? There were the love letters about sweet childish things: how one day his woman would make his house a home, generalities mostly, and two children now between them, another on the way.

The Yellow House

The Yellow House